|

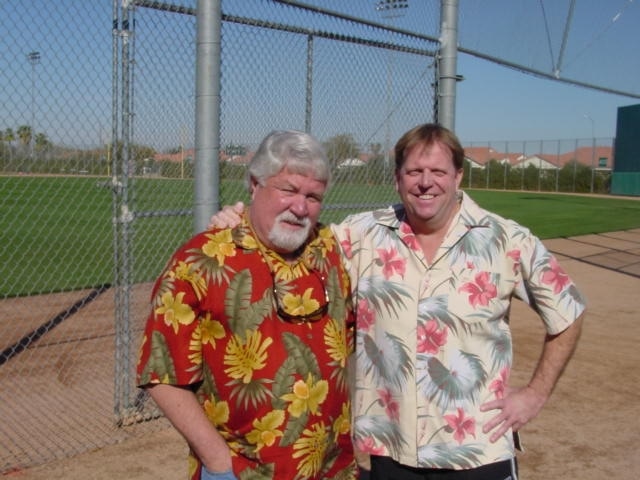

Any time I have a chance to use this classic photo, I’m going to do it.

On the right, that’s Jim Hendry, the man who invited me to move from media relations into the baseball operations department – and gave me a diamond-side view to the inner workings of what it takes to put together a baseball team. On the left, that’s Gary Hughes, the man who saw something in Jim to help launch his professional baseball career. Gary – also known to his legion of fans as Boomer – has helped launch a bunch of careers and has been a friend to multitudes both inside and outside the game. I had the pleasure of working closely with him during my time in baseball ops, and he continues to be a sage source of advice and guidance for me. How connected is Boomer in the industry? Mr. Hughes first began working in professional baseball in 1967. That’s 50 full years of service scouting for the San Francisco Giants (1967-72), New York Mets (1973-76), Seattle Mariners (1977), New York Yankees (1978-85), Montreal Expos (1986-91), Florida Marlins (1992-98), Colorado Rockies (1999), Cincinnati Reds (2000-02), the Cubs (2003-2011) and the Boston Red Sox (since 2012). For those of you who don’t know him, his career honors include being selected by Baseball America as one of the Top 10 scouts of the 20th century. He also was inducted into the Professional Baseball Scouts Hall of Fame in 2008. But it’s not because of baseball that I’m writing about Gary today. OK, it is about baseball, but more in the “What Could Have Been, But Wasn’t” category. The NFL draft is coming up this week, and Gary kinda-sorta has a hand in it – as he has been directly connected to a pair of football executives: John Elway, executive vice president of football operations/general manager of the Denver Broncos, and John Lynch, the general manager of the San Francisco 49ers. Hughes was involved in the signing of both to play baseball – as a Yankees scout in 1981 (Elway was selected in the second round with the 52nd overall pick) and as the Marlins’ scouting director in 1992 (Lynch was Florida’s second pick in the Marlins’ first-ever draft). Elway was attending Stanford University en route to a Hall of Fame career with the Denver Broncos. “John was eligible to be drafted in baseball as a sophomore, and we did not have a first-round pick; as we often did in those days, we signed a free agent,” Hughes said. The Yankees surrendered their first pick to the Padres as compensation for the signing of Dave Winfield. “I was in my third year as a full-time scout, and here I am talking to George Steinbrenner while the president, the scouting director, the player development director and the GM all sat there – listening to me talk to him. “George was infatuated with the idea of drafting John Elway. I said to him, ‘We don’t have to take him this high; he’s probably going to play football. Nobody is going to take him this high.’ “And he said, ‘Yeah, but.’ And his ‘Yeah, but’ made sense. “In those days, after the first and second round, the draft was shut down for a secondary phase for those who were passed over the year before or were drafted and didn’t sign. Mr. Steinbrenner said, ‘What will happen is, everybody will look at their board, and they’ll see how their boards have been beat up, and Elway will look awfully good to someone picking in the third round.’ He had a point there. Then he said, ‘So we’re going to take him.’ “And then he said, ‘He’s got to play baseball.’ And I said, ‘Whoa. Listen, I just got this job. I don’t want you to come back and say I said he’d play baseball only. There’s a very definite chance he’s going to play football.’ And he said, ‘Duly noted.’ “That took me off the hook. So we drafted him with our first pick.” Due to the timing of when Elway and the Yankees agreed to terms, he didn’t play baseball until the following June with Oneonta in the New York-Penn League. He started his pro career 1-for-19, and when he left six weeks later to return to Stanford for football practice, “he was leading the team in every offensive category – including stolen bases,” Hughes said. “He showed power. He showed speed. It was exciting to see that he could do all that.” A rightfielder, Elway batted .318 with four homers, 25 RBI and 13 stolen bases in 42 games for Oneonta. After a stellar senior season at quarterback, it became evident that Elway could be the first player selected in the 1983 NFL draft. As has been well documented, he informed the Baltimore Colts before the draft that he wouldn’t sign with them if they drafted him first overall; they did, and he held his ground. “Shortly thereafter, I took John and a couple other guys fishing,” Hughes said. “I was talking to him on the boat, and I asked him, ‘What are you going to do now?’ “He said, ‘If they don’t trade me, I’m going to play baseball.’ “I basically told him, ‘You’re full of baloney,’ or some such language. And he said, ‘I’m not kidding. I’m not playing for Baltimore. If they don’t trade me, I’m playing baseball.’ “Not much later after that, they traded him to Denver. The rest is history.” How good of a baseball player could Elway have been? “He could have had a long and successful career,” Hughes said. “The ability was there. He could run. He had power … a left-handed hitter with power at Yankee Stadium. He would have played a long time. Obviously, he had a good arm. He could play rightfield. It just didn’t work out for us. But I think George was happy with the outcome. He was happy that there were a lot of headline stories.” Lynch’s story was, indeed, a completely different story. Like Elway, he attended Stanford. Unlike Elway, he quit football to concentrate on baseball. “We drafted him, we signed him, and he goes out and ends up pitching the first game of the season (for Erie) – which made him the first pitcher in the history of the Florida Marlins’ organization,” Hughes said. A right-handed pitcher, Lynch made nine minor league starts in 1992-1993 for Erie of the New York-Penn League and Kane County in the Midwest League. “Dennis Green was the football coach at Stanford – but then he left to become the coach of the Minnesota Vikings. When he left, Bill Walsh came back, and John came up to me and said, ‘I know I told you I quit, but I always wanted to play for Bill Walsh. Can I at least go back and play?’” Walsh, a legendary coach, is best known for leading the 49ers to three Super Bowl championships. “I said, ‘John, I can’t stop you from doing anything. We’ll see you next spring,’ Hughes said. “Well, next spring never occurred. He played, and Bill Walsh let the NFL people know just how good he was.” A safety on the gridiron, Lynch was selected by Tampa Bay in the third round of the 1993 NFL draft. He went to nine Pro Bowls in 15 NFL seasons – and has been a finalist on the Pro Football Hall of Fame ballot four times. “He had a strong arm. Obviously, he was a good athlete. He never really had a chance to develop to see how good he might have been,” Hughes said. “We were excited to get him. He threw hard. But we lost him to Bill Walsh.”

1 Comment

This is the third installment in my impromptu mini-series about Billy Blitzer.

You can read the initial story here: http://www.chuckblogerstrom.com/all-my-stories/it-coulda-happened-it-shoulda-happened-it-did. You can read the second story here: http://www.chuckblogerstrom.com/all-my-stories/the-book-of-blitzer-chapter-2. ***** Billy Blitzer was rattling off the names of players he signed who made it to the major leagues. He’s had a dozen, which is a lot coming out of his “cold weather” region (New York/New Jersey/New England area) – including first-round picks Shawon Dunston, Doug Glanville and Derrick May. The conversation soon turned to “his guy.” “You’re fortunate if you sign players that play in the big leagues. But you’re very fortunate if you sign a player that you’re specifically associated with,” Blitzer said. “For years, whenever I walked into the park, people would say ‘There’s the scout who signed Shawon Dunston’ – especially in New York. But then, as the years went by, as I go around the country – even among baseball guys – I hear ‘There’s the scout who signed Jamie Moyer.’ “Scouts used to kid me, because when they’d have to see a soft-tossing lefty, they’d tell me, ‘It’s all your fault. If you hadn’t signed that kid, we wouldn’t have to bother seeing this other kid pitch.’ Jamie became the figure for people to have to write reports about … a soft-tossing lefty. And his name would go on people’s reports. Being the person who signed Jamie, they’d ask me, ‘What did you see in him?’” ***** 1984 is well known in Cubs annals, as it was the year the Cubs went to the postseason for the first time since World War II. While I can still envision watching Rick Sutcliffe strike out Pittsburgh’s Joe Orsulak to send the Cubs to the playoffs, that wasn’t the only success for the Cubs that year – as the scouting department drafted a duo that went on to record 624 major league victories. As Blitzer succinctly sized it up, “What a draft that was … Greg Maddux in the second round and Jamie Moyer in the sixth. You can’t do better than that.” Blitzer was all-in on Moyer from the first time he saw the left-handed pitcher on the St. Joseph’s University baseball team. Moyer was not the type of pitcher scouts were typically drawn to – a soft-tossing southpaw who pitched in a northern cold-weather area. Blitzer ignored the fastball velocity when he scouted Moyer. He looked at the total picture. “What I saw was pitchability. I just had a gut feeling. Every time I’d see this guy go out and pitch, he’d do everything he could to get hitters out. He just had a feel for what he was doing and a feel for his craft, and I was just drawn to him.” The scout followed the pitcher from afar, watching him work and doing his behind-the-scenes due diligence in learning about background and makeup. That spring, Moyer went 6-5 with a 1.82 ERA in 12 games for St. Joseph’s, completing seven of his 10 starts. He’s still a legend there; he’s on the cover of the university’s 2017 baseball record book. “I submitted my report on Jamie, and (scouting director) Gordy (Goldsberry) called me up,” Blitzer recalled. “He said, ‘You know, I just read your report. You seem to have a real good feel for this kid. Tell me about him.’ And I did. And I verbally told him what I felt about him, what I saw in the kid. (Cross-checker) Frank DeMoss then went in and saw him – and Frank took a liking to him, too. We just went from there.” Moyer was aware scouts were at his games, but he paid little-to-no attention to it. “I knew there were scouts, but they didn’t really talk to you – and I didn’t really have any conversations with any of them,” Moyer said. “At that point, I didn’t know who Billy Blitzer was. “Right before the draft, miraculously … I lived in a house with a bunch of other students and we had a pay phone. Somehow, he got that phone number. The pay phone rang, and someone said, ‘Hey Jamie, phone call for you.’ I went over, and this guy says, ‘Hi, I’m Billy Blitzer with the Chicago Cubs, and I’ve been watching you. We’re interested in you.’ We had some small talk, and then he asked, ‘What’s it going to take to get you out of school?’ It was my junior year. I laughed. I was green. I couldn’t talk. ‘I don’t know.’ I’m thinking, just hand me a contract and I’ll sign it. I wanted to play pro baseball. “That conversation kind of ended. There were no guarantees. Fortunately, Billy wrote me up well enough.” The draft was held in early June. While Blitzer wasn’t physically in the Cubs’ draft room, DeMoss – his regional cross-checker – was. “Frank was the one who spoke up for Jamie – but Gordy already knew,” Blitzer said. “Gordy knew that Jamie was my gut guy. I’ll tell you, there were only two scouts that really liked him – myself and a scout with the Phillies. Thank God we got him.” Moyer was selected in the sixth round – the 135th overall pick in that year’s draft. “Billy called me in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I was playing for the Harrisonburg Turks in the Shenandoah Valley League,” Moyer said. “I had been there about a week, and I might have pitched in part of one game. The draft came, and it wasn’t like it was today – a TV show and everything on the internet. Back then, there was just a baseball draft. “So I got a phone call where I was staying in Harrisonburg. ‘Hey Jamie, this is Billy Blitzer of the Chicago Cubs. Just wanted to let you know we drafted you in the sixth round.’ As you can well imagine, I almost dropped the phone on the floor. I was ecstatic. I’m like ‘OK. What do I do? Where do I go?’ I was going 100 miles per hour. “And Billy goes, ‘Slow down. Take your time. Get yourself back home. Give it a couple days. When you get home, I’ll drive down. I’ll meet your parents. I’ll sit down and we’ll discuss things. “A couple days later, I got home, and that’s the first time I met him face-to-face.” ***** Let’s call this “The Art of the Negotiation – Billy Blitzer style.” Moyer: “Billy had his little brief case, and he walked into our house. He was very kind, very respectful. And he just chatted with me and my parents – and told us about the organization. He gave us his little shtick.” Blitzer: “In those years, there were no negotiations with the front office; it’s not like it is now. You had one phone call to make. And when you made that one phone call and asked for extra money, that was it. You couldn’t ask for a couple thousand dollars, then call the front office back later on and ask for a couple thousand more on top of that. That was a no-no. You had one call.” Moyer: “He asked, ‘Do you want to sign?’ Of course I did.” Blitzer: “I can still picture this … we sat at the kitchen table. I’m at one end of the table, Jamie’s opposite me. His mother was on my right. His father was on my left. And I offered him $10,000.” Moyer: “I’m like, ‘Oh boy.’ My parents said, ‘It’s your decision. We’ll support you however you want.’” Blitzer: “I tell him I had one phone call to make. Now, we’re talking back-and-forth, and I said to him, ‘OK, if I make that one phone call, will you sign for $12,000?’ And when he looked like he would do it, he starts hemming and hawing.” Moyer: “Welllllll … can you give me a little more money?” Blitzer: “He says to me, ‘I think it will have to be $15,000.’ I said, ‘Thinking is no good.’ I went to stand up; I put my hands on the table, and said, ‘I don’t think you know what you want. I’m not making that phone call. I’m leaving …’” Moyer: “He closed his brief case and said, ‘I just need to let you know … if I leave your house and you don’t sign, I may never come back.’” Blitzer: “As I said ‘I’m leaving,’ an arm reaches across the table. It was Jamie’s mother. She grabs my right arm and said, ‘Mr. Blitzer, don’t get excited. Don’t leave. He’ll sign.’ I look across the table and said, ‘Are you going to sign, or am I wasting my time here?’ Jamie says, ‘Don’t leave. I’ll sign, I’ll sign. Make the phone call.’” Moyer: “He gets on the phone with Gordy, and they start talking. Then he gets off the phone and says, ‘Well, you know, we can give you a little bit more money, but I don’t know how much further we can go than that.’” Blitzer: “I made the phone call, Gordy gave me an extra $3,000, and we agreed on $13,000.” Moyer: “Well … I signed, and a day or two later I flew out to Arizona for the mini spring training. That was 1984; in 2012, I was done.” Blitzer: “Can you imagine signing a guy in the sixth round for $13,000? And then he goes on to win 269 games. But that’s the way it was back then. He wanted to play, and I knew he wanted to play.” Moyer: “It’s funny. I kept in touch with Billy; we have a very good relationship. I would see him when I was playing, whether I was with the Cubs or other teams during my career. I’d go to New York, and we’d go out to dinner and things like that. And we’d go back and discuss when he came to the house and all that kind of stuff.” Blitzer: “We’ve been close ever since. Really nice family. Really nice people. Like I said, I’ve always been considered part of the family ever since that day.” ***** Jamie Moyer, on Billy Blitzer … “Who do think was the first guy I called when the Cubs won the World Series? Billy Blitzer. And this guy was crying on the telephone. How awesome is that? If there’s somebody that bleeds Cubs blue, it’s Billy Blitzer." I started with the Cubs as a media relations intern back in 1986. On my third day on the job, Jamie Moyer joined the team after being recalled from Triple-A. In my first “official” act as a Cubs intern, I got to help him carry his luggage and equipment to the clubhouse. That’s what interns do. Two days later – on Monday, June 16 – Moyer made his major league debut, working 6.1 innings and earning the win over the Philadelphia Phillies 7-5. He not only defeated his hometown team, but he was opposed by Steve Carlton – who was in the twilight of his career (he would pitch through 1988). Now, think about that matchup for a moment.

Moyer pitched for the Cubs from 1986-1988 before being traded to Texas as part of the infamous Rafael Palmeiro deal. He had his greatest success in Seattle, recording a pair of 20-win seasons (as a 38-year-old and as a 40-year-old) and going to the 2003 All-Star Game. At the age of 45, he was a 16-game winner for Philadelphia – and got to celebrate when the team of his youth won the 2008 World Series. As I said, I met Jamie the first time he walked into Wrigley Field as a member of the Chicago Cubs, helping him drag his luggage and baseball equipment through the ballpark’s concourse. I joke that it was my first official act. Realistically, my first official act took place about 45 minutes after his major league debut, when – in the Cubs clubhouse – Jamie called me over; he wanted me to find his dad and bring him to the locker room. Reuniting a father and son after the son’s first big league win is an awesome moment to rewind in my head. I recently spoke to Jamie for the series of stories I’ve been doing on legendary scout Billy Blitzer – the scout who signed Moyer. You’ll get to read the scout/player piece later this week. After talking about Billy, we talked about various subjects – including the many things Jamie witnessed over a professional career that spanned from 1984-2012. What was it like being a dad when baseball was your vocation?

Jamie Moyer: “I tried to be involved when I could, but my family understood what I was doing and where I was. I was supporting a family, and this job took you away seven months of the year. In the off-season, you had to work out and stay in shape. I had leeway, but we had a lot of great experiences through the opportunity of me playing baseball. I took my boys to the ballpark when they were little. I took them as they got bigger. I took them when they were in high school and in college. It’s been a family experience. “When I was with the Phillies, any time we had a clinching game – as we got towards the end of the game, our boys came down to the clubhouse and put a uniform on. When that third out was made, they were in the dugout with their dad, and we celebrated … and we celebrated with teammates … and we celebrated in the clubhouse. That’s something really special that I had with my boys. You can take all the money and the notoriety and all that, but we had that special bond. I was also able to celebrate with the rest of my family and my parents. “I would have loved to go to the World Series with every organization I was in, but if I could pick one, it happened in a magical way. It happened in 2008 in Philadelphia, where I was raised. I went to college there. My parents were there; they were able to witness it. My sister was there. My family was there. It was pretty special. In 1980, the Phillies had won their last World Series. I was a senior in high school, and I skipped school to go to that parade. Then in 2008, I was in the parade, going down Broad Street. Pretty cool.” That would have to be No. 1 among your career highlights. “Oh, yeah. But I feel like for me personally, I have a lot of highlights. My first major league start … Wrigley Field. And who was it against? The Philadelphia Phillies and Steve Carlton, my idol. That was pretty magical. Witnessing Nolan Ryan’s 300th career win; that was an unbelievable milestone. I’ve had the good fortune to play with some other 300-game winners: Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux. I played against Tom Glavine. Honestly, when are we going to see another 300-game winner? “So to have the opportunity to be a witness to that … and I witnessed two of Nolan Ryan’s no-hitters. I witnessed his 5,000th strikeout; that’s a pretty big number. I was a teammate of Cal Ripken’s when he broke Lou Gehrig’s streak. I mean, some pretty monumental things in the game – and I had the good fortune to be there. I’ll always appreciate and respect that – because those feats were not easy to accomplish. And I was just a small, small, small piece of it. “I was on the team that played the first night game at Wrigley Field. Pretty cool. And I was fortunate enough to play on an all-star team that went to Japan. Again … pretty cool.” The longevity of it certainly helped. But you had your own accomplishments, too. “Personally, being a 20-game winner twice was pretty special. I won 20 and 21, and it wasn’t an easy feat. But I didn’t do it alone. I had teammates that allowed me to accomplish that. They caught the ball, they threw the ball, they hit the ball. They ran bases. They played every day. They played hurt. And then, two years ago, I was elected into the Seattle Mariners Hall of Fame. I never expected something like that to happen to me. “Back in 1984, if you would had asked me, ‘Do you think you’ll play until your 49 years old?,’ I probably would have said ‘Yeah, I’d love to.’ But you know, not until I played with guys named Charlie Hough and Nolan Ryan in Texas, and saw them at their ages – in their 40s and still playing – that’s when I started thinking, ‘Man, someday I hope I can do that.’ I enjoyed it. I loved the game. I had passion for the game. I loved being around it. I loved the challenges. Sometimes, the challenges were pretty tall, but you figured out a way to get through it. Being around guys like that … you watched them get through it. You watched how they worked. You watched how they were as teammates. You can really learn a lot by using your eyes and your ears, and that’s what I learned how to do as I went through my career. “As I got older, I became far more appreciative of opportunities and playing and teammates and coaches. That comes from maturity. I’m not tooting my own horn … it’s reality. I could have been a knucklehead and just closed my eyes to all of it and just said, ‘The heck with everybody else. It’s all about Jamie.’ But I didn’t view it that way. It takes 25 guys and a coaching staff and an organization. It goes from the parking attendants to the players to the front office to the fans to the ownership. And then you have to have a community that supports it.” It’s been five years since you last played. Do you miss putting on a uniform? “Yes and no. I went up to Seattle for Opening Day, and it was a lot of fun. It brings back a lot of great memories. It brings back a lot of warm fuzzy feelings. But then you start thinking about the travel and the soreness and the stiffness and the aches-and-pains and being away from family. I’m a little bit older, and I realize my body can’t do it anymore. My mind says, ‘Oh yeah, let’s do it.’ But my body says, ‘Yeah, you go do it. But we’ll sit here and watch.’ I know that I can’t, but I do miss it. I do miss seeing the guys. When I went to Seattle, I saw some ex-teammates. We laughed and joked and had a good time. We reminisced. But that’s kind of where it stops and starts.” Tell me about all your kids. “Dillon is 25. He’s out of baseball now and working in real estate in Seattle (note: Dillon, a former infielder, played four years of minor league ball). Hutton is 23, and he’s in Double-A with the Anaheim Angels. He’s in Mobile, Alabama, right now (note: Hutton, a second baseman, was the Angels’ 7th-round pick in the 2015 draft). Timoney is 21, and she’s going to graduate from St. Mary’s College in South Bend in December. And Duffy is 19. She’s currently a sophomore at Santa Clara University, where she plays soccer. “McCabe is 13 and he’s in seventh grade. Grady is 12 and she’s in seventh grade. Katilina is just turning 11 and she’s in fourth grade. Yenifer is 10 and she’s in fourth grade. “So we have two out of college, two in college and four in elementary school.” I know you still keep in touch with Jay Blunk (a former Cubs intern who is now an executive vice president with the Chicago Blackhawks). When you first reached the majors, you shared an apartment with him. In this day and age, how often do you think a major league player shares an apartment with a media relations intern? “Yeah, how about that? Crazy. I don’t know if that’s happening too often. And now he’s a world champion. He’s a hockey specialist, and he doesn’t know which end of the stick to hold. But it was great. I enjoyed meeting Jay and our relationship and the fun we’ve had over the years. Jay is a great guy.” For me, it’s hard to believe for as long as your career was, you only spent a short amount of time in Chicago. But a whole lot of people remember you from your time here. “I really enjoyed Chicago. The fans … Wrigley Field. We obviously didn’t play the way we would have liked to have played. We played like many of the other teams played for over 100 years. But it was fun to watch the World Series last year, watching from afar and seeing the excitement – and seeing the city take it in. “And my old teammate, who got called up to the majors with me – Dave Martinez – he was the bench coach. How cool was that? And another teammate, Chris Bosio, is the pitching coach. I played with Chris in Seattle.” You played long enough, it’s sort of like “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” “Yeah, there are a lot of connections. But when you play for 20-some years, it’s going to happen. That’s the fun part about it.”

Shawon Dunston (photo credit: Wikipedia)

It was my last organizational meetings with the Cubs … early 2012 … Mesa, Arizona. The new regime was in its first year of running the Cubs. There were a lot of new faces in these meetings. But at one point, Theo Epstein asked Billy Blitzer – one of the elder statesmen of the Cubs, having been in the organization since 1982 – to get up in front of the group and talk. After an impassioned speech from the heart, “I put my left hand in the air and I said to everybody, ‘Look, no ring. I have nothing to show for this. I’ve been here 30 years; I have no ring on my finger,’” Blitzer said. “’You people have to help me put a ring on this finger and your own fingers, because I don’t have another 30 years to give.’ When I said that, the entire room exploded.” ***** The last time I wrote about Billy Blitzer, I might have accidentally lied to you. My initial blueprint was to drop a few short nuggets about Billy – a scout in his 35th year with the Cubs – as an appetizer to an extended story about him. The more I’ve thought about it, I realized it would be impossible for me to write a piece about Billy in the 2,500-word range – which is on the longer side for keeping someone’s attention. Heck, I can’t keep some of Billy’s stories to 2,500 words. So I’m veering from my original plan, opting instead to writing several chapter-like pieces about Mr. Blitzer. This way, I can give his stories justice – and you’ll get a better opportunity to read about him and enjoy some of the tales about this man’s career and livelihood. You can read the earlier story here: http://www.chuckblogerstrom.com/all-my-stories/it-coulda-happened-it-shoulda-happened-it-did. I hope you enjoy reading about how Billy got his start in the game and with the Cubs. ***** The year was 1975. Like most students in college, Billy Blitzer was trying to figure out what he would be doing for his vocation. He was a student at Hunter College – located in the Upper East Side of Manhattan – and he was playing baseball. He also was coaching a sandlot team that summer. As fate would have it, one day, while coaching this sandlot team, a scout happened to come by and sat down next to Billy. “I didn’t know who he was. He was just an old man sitting next to me,” Blitzer said. “I say old man, but I’m probably older now than he was then. But to me, he was an old man. “We started chatting, and he says to me, ‘What are you doing here?’ “I said, ‘I’m going to coach the next game.’ “He said, ‘I’m going to watch.’ “OK. I didn’t care … he could watch. When the game was over, he came over to me while I was packing the equipment. He said, ‘I want to talk to you.’ “I said, ‘About what?’ “He says to me, ‘Well, my name is Ralph DiLullo, and I’m a scout with the Major League Scouting Bureau.’ “I said, ‘What’s that?’ That was the first year the Bureau started. I didn’t know what the Bureau was; nobody did. And he explained to me what it was. Then I said, ‘Oh, you want to talk to me about my shortstop?’ I said that because my shortstop ended up playing in the big leagues. He had a cup of coffee with the Brewers; his name was Willie Lozado. “And he says, ‘No, I want to talk to you about you. You’re coaching kids your own age.’ I was only two years older than these kids. ‘You seem to know what you’re doing. I want you to give me your phone number. I’m going to call you. I’m going to find out when you’re playing next week, and we’re going to sit at a game together.’ “I said, ‘Why?’ “He said, ‘Don’t worry. Just give me your phone number. I’m going to call you.’ “I went home and told my parents what had happened. I said, ‘I don’t know if this guy is on the level or if he’s a nut or whatever.’ “He called me, I went down and met him, and he was pointing things out to me on the field … what to look for. And he said to me, ‘You’re going to run a tryout camp in Brooklyn. I’m going to run it, but you’re going to invite all the players. And then you’re going to help me in Jersey when I run my camps and this and that.’ That’s how I started. “But the ironic part is … Ralph DiLullo, before he went to work for this new Major League Scouting Bureau, worked for the Chicago Cubs for 25 years. Ralphie signed Bruce Sutter and Joe Niekro. He was a very prominent scout.” When DiLullo left to go to the Bureau, the Cubs didn’t hire anybody to serve as the amateur scout in the region, opting instead to use information provided by the Bureau scouts in that area – DiLullo and former Cub Lennie Merullo, who was based in New England. If a Bureau report indicated there was a player worth checking out, Cubs cross-checker Frank DeMoss would run up and down the East Coast. DiLullo continued to mentor Blitzer – who went on to spend his first seven years of scouting with the Bureau. It gave him an opportunity to hone this craft at a young age – and to start to make a name for himself. “A lot of scouts used to be afraid to come into New York City. They’d come in packs; they’d come in groups,” Blitzer said. “So I went to work for the Bureau. My first four years, I was an associate. Then they hired me under contract. I had New York, Long Island and Westchester. And in the short time I was under contract, I found Bobby Bonilla and Devon White and Johnny Franco and Frank Viola and B.J. Surhoff and Walter Weiss. There were others, but those were the big, big names. Scouting directors from different organizations started telling their scouts, ‘You better get into New York City. This kid is coming up with players.’ “When I came up with Weiss, I remember a scout from a club saying to me, ‘Where are you finding these guys? We never come up here.’ “I said, ‘You’ll be coming up here from here on in.’ For those of you not familiar with the Major League Scouting Bureau, Blitzer wasn’t the one who eventually signed those players. His job with the Bureau was akin to being a bird dog. He went into the trenches and flushed out the talent through his Bureau reports – which went to all the major league teams. It was up to individual teams to decide if they wanted to come in and see for themselves. But the talent he was uncovering speaks for itself.

“You see, I wasn’t afraid to go into a lot of places, because I grew up in New York City,” Blitzer said. “And I played on a lot of these fields. And the team that I coached in the Youth Service League – that’s where Shawon Dunston was my bat boy when he was a kid, ironically; that’s how I had my in with the Dunston family when the Cubs were trying to sign him. “But I wasn’t afraid to go into these places. A lot of these kids on my team played in these leagues in tough areas and they would tell their coaches, ‘Listen, Billy Blitzer is coming up. Make sure you keep an eye on him and nothing happens to him.’ You know, South Bronx, places like that back then were tough areas to go into. And I went in and I found players.” And one of those players – Dunston – he literally watched grow up. ***** In 1982, the first year of the new Dallas Green regime, the Cubs had the No. 1 overall selection in the country. With a new hierarchy in place, more scouts were added, and for the first time since the Ralph DiLullo years, the Cubs utilized a full-time area scout in the New York area named Gary Nickels. Shawon Dunston, an infielder at Thomas Jefferson High School in Brooklyn, was at the top of the Cubs’ draft list. As a senior, he batted .790 and went 37-for-37 in his steal attempts. The Cubs wanted all the background and makeup information they could get on him, and Blitzer became a valuable resource. Blitzer was still working for the Major League Scouting Bureau that June, and, prior to the draft, the Cubs sent a letter to the Bureau asking for permission to have Blitzer go out with Nickels to negotiate a contract with Dunston and his family. “Like I said, I knew Shawon since he was 11 years old,” Blitzer said. “Mel Zitter, who ran the Youth Service League, and I taught him how to play. “When it came to negotiate the contract, I’ll never forget. Gary and I went into the house on the Saturday before to start to talk to them. The draft is Monday. Gary and I go in, it was a rainy kind of day, and the Dunstons had the old Game of the Week on NBC on – and who’s playing that day, the Chicago Cubs. “Gary and I sat in the Dunston’s home and read the entire contract to them. It was the old standard contract, and we read it paragraph after paragraph and explained the entire thing. It took us a couple hours. At the end, Gary pretty much made an offer to the family – and they said that everything would be OK.” These were definitely different times. Think about it. A high school kid who could go No. 1 overall in the draft, and the area scout was in the family’s home for a face-to-face money meeting. “Because Shawon could be the No. 1 pick in the draft from the No. 1 media capital in the world, people were calling his home. People were calling my home to see if this was going to happen,” Blitzer said. “So what we did … Gary planned for all of us to go into Manhattan and stay in a Sheraton Hotel, and he registered the rooms under different names. Gary and I were in one room and the Dunstons had a suite. “But on that Sunday morning, I pick up the New York Daily News, and Dick Young – who was the big columnist at the time – had quotes in his column from a scout by the name of Dutch Deutsch. Dutch was the scout who signed John Candelaria and Willie Randolph. Well, Dutch comes out in Dick Young’s column and says ‘Shawon Dunston is the best player to come out of the New York area since Carl Yastrzemski.’” Yastrzemski, who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1989, was from Long Island. “I see that in Sunday’s paper and I’m going, ‘Uh oh. We can be in trouble,’” Blitzer said. “I was supposed to meet Gary at a McDonald’s near the Dunston house, then we were going over to the house. Then Gary was going to go into the city and get the rooms, and I was going to wait in the Dunston house while his mother and his sister were going to the beauty parlor – because there was going to be a press conference on Monday at the commissioner’s office after he was drafted. “Gary and I go into the house, and it was like we walked into a refrigerator. They were really cold, because they felt we were cheating them; we weren’t giving them enough money. And I could see there was a problem, so I said, ‘Mr. Dunston, let’s go into the other room. Just you and I. We need to talk.’ “Mr. Dunston and I went in and spoke, and I explained to him what was going on. I said, ‘You can’t listen to everything in the newspaper. You don’t realize how important it is that Shawon goes first in the country. If the Cubs don’t take him and he goes second or third, he might never be remembered. But he’ll always be remembered as the first pick. That will mean more for him down the line. Endorsements, things like that. It doesn’t mean anything right now.’ He agreed with me, and we walked out. He said to Gary, ‘OK, we still have a deal.’ “So Gary leaves to go into Manhattan. Now remember, there’s no cell phones. I’m hanging around the Dunston house, waiting until his mother and sister come back from the beauty parlor. I had a little Chevy Nova, and I drive all of them into Manhattan. I go to the Sheraton where I think that Gary is – because that’s where the Baseball Writers (Association of America) have their dinner. I drive in, I pay for the parking in the hotel. Before we had left, Gary had called the house and told us what room he was in. He had all the keys. “So we go up to the room with our overnight bags, I knock on the door, and somebody who doesn’t speak English opens the door. I’m thinking, maybe he gave us the wrong room. “So we all go down to the front desk, and I give them the assumed name that he checked in under. The guy at the front desk says, ‘There’s nobody at this hotel by that name.’ I said, ‘There has to be. He’s in the Sheraton. I spoke to him.’ He said, ‘There’s another Sheraton four or five blocks away. Let me call over there.’ Sure enough, that was it. “Now I’m not taking my car out of this Sheraton because I’ve just paid for the parking. It’s not cheap in New York. “So here we, the Dunstons and Billy Blitzer, walking down Broadway with our suitcases to go to the other Sheraton. “The next day, Shawon was drafted – of course. We had the news conference; Gary handled everything. And the rest is history.” Dunston made his major league debut in 1985 and played for 18 years, batting .269 in more than 1,800 games. He was a two-time National League all-star and went to the World Series in 2002 in his final big league season. Does Blitzer ever think about what might have been if Ralph DiLullo hadn’t shown up that one day … or if Shawon Dunston was born a year older – making him draft-eligible before the Dallas Green era started in Chicago? “Yes. I tell people Billy Blitzer wouldn’t exist in the world of baseball. I probably would have been a coach some place. “People always say, ‘How did you get in? Usually it’s people that played.’ And I tell them, ‘The fickle finger of fate touched me on the shoulder.’ If Ralph DiLullo doesn’t sit next to me at that park, probably none of this ever happens. It was just something that was meant to me.” As for being in the right place at the right time with Dunston, “That’s how I met Gary Nickels,” Blitzer said. “Who’s to say I wouldn’t have met him? But really, that’s how we got close. Gary had to do his homework and get as much information as he could about Shawon, and I was the perfect person. “When we all went through this, there was no job promised to me or anything. That came after. They just saw the way I handled myself and they saw my track record. They read my reports from the Bureau. Here I was a young scout, but I had seven years’ experience already. I’m still a young man, and I had success. So I was the right person for Dallas’ group. He wanted a mix of young scouts and older scouts.” With the Cubs opening the season in St. Louis and Milwaukee, I couldn’t help but think about old Busch Stadium and Milwaukee County Stadium.

I say that because there’s just something about the older cathedrals. That’s why all the work being done on Wrigley Field is magnificent; there’s something grand about modernizing the structure while keeping its charm alive. Now in the case of old Busch Stadium, charm isn’t the first word I’d use to describe it. In reality, the ballpark had more than its share of great moments. While it wasn’t a St. Louis original – in fact, it was one of the multipurpose late 1960s cookie cutters – it still created a lot of memories for me. Unfortunately, most of them were bad. When I think of old Busch Stadium, I think of a lot of last at-bat losses … and a lot of Cardinals little ball with bunts and repeated successful hit-and-run at-bats where they would nickel-and-dime you to death … and Mark McGwire hitting home run No. 62 in 1998 to surpass Roger Maris’ single-season record . But I also think of playing in a ballpark smack dab in the middle of downtown … and staying in a hotel directly across the street from the ballpark … and seeing my brother, who went to St. Louis for med school and never left … and the Missouri Bar and Grille, a famous baseball hangout just blocks away from that area. Thanks to the hotel-to-ballpark proximity, it was at the Marriott that the following humorous event took place. Harry Caray – and this was probably the only time I ever saw him going to the ballpark early on the road – stopped me before I left for the stadium and said that his driver knew a shortcut. He told me to hop in the car with them. Remember, you could see the ballpark from the hotel’s side entrance; it was directly across the street. I knew this ride could be interesting. I repeat this again – the hotel was directly across the street. Imagine the corner of Clark and Addison, looking across at the Cubby Bear. It was that close. I got in the car with Harry on the hotel’s curb side. The driver looked around, backed up around 100 feet, then pulled forward to the other side of the road and let us out. That was the shortcut. We were in the car less than a minute. Anyway … old Busch Stadium was where I had one of my great fandom days. September 23, 1984. I was in my sophomore year at Missouri, and the Cubs were closing in on the National League East Division title – their first foray into the postseason since 1945. A group of us made the 125-mile pilgrimage from Columbia to St. Louis for a Sunday afternoon Cubs/Cardinals doubleheader. I don’t have to go into great detail, but it was one of those days that had special meaning. In Game 1, Steve Trout went the distance in an 8-1 win. In Game 2, Dennis Eckersley pitched the Cubs to a 4-2 victory. The Cubs left St. Louis with a magic number of 1 – and Rick Sutcliffe memorably closed it out the next night in Pittsburgh. Meanwhile, Milwaukee County Stadium was where I had my first beer at a baseball game. So of course it’s one of my favorite baseball venues. It was the summer of 1983. It was only a few weeks after I graduated high school. Using basic math, that meant I was 17. Three of us drove up to Milwaukee for the weekend – as my friend wanted to show off Marquette University, where he would be going to school. We took in a ballgame at County Stadium, and on my pregame trip to the concession stand, I placed a food order. The guy taking my order then asked, “Do you want a Miller with that?” I thought he was joking. I played along and said yes. And then he filled up a large cup for me. Needless to say, warm night/cold beer was a nice combination. I’m still waiting to be ID’d. For the most part, the Cubs played well during my work trips to County Stadium – notwithstanding the famous Ron Santo “Oh nooooooo!” when Brant Brown misplayed a fly ball in 1998. It wasn’t the torture chamber that old Busch Stadium seemed to be. County Stadium had an old-time feel to it, even though it was built in the 1950s. There was something about pulling up and seeing all the tailgaters … and the smell of the brats on the grill … and the Secret Sauce – so secret that the ingredients are listed on the bottle … and the first iteration of Chicago Cubs North fans in the crowd. Even back in the day, it was like being home away from home. The new Busch Stadium is a really nice facility. Miller Park really grew on me. Both locations are just steps away from the old facilities. But in the memory bank, it’s hard to replace the parks that guys like Eddie Mathews and Warren Spahn and Bob Gibson and Ozzie Smith called home.

Billy Blitzer / Photo Credit: New York Daily News

Some of the best storytellers in the world sit behind their laptops and craft stories in small words and abbreviations and with lots of punctuation – or no punctuation at all. They write stories so that the people reading them can visualize what they are saying. I’m talking about baseball scouts who, in writing scouting reports on players, have to paint a picture with their words – and in lingo that their bosses can understand. When they’re not behind the computer screen, they’re behind the home plate screen – watching games and watching practices and watching players in their warmup routines. It’s where a scout learns about players – their makeup, how they interact, how they act, how they dress, how serious they appear. Those mental notes formulate the stories that are told to the front office – and the stories they share with others. Last week, I caught up with the legendary Billy Blitzer – a longtime Cubs scout who was about to depart Florida after spending a month in spring training. I’m working on a longer-form story about Blitzer – pronounced Blit-zuh in his native Brooklynese – who is beginning his 35th season with the Cubs and his 42nd overall as a scout. This year, making that trip to spring training was a big deal for multiple reasons. Blitzer has fought some major health issues the last two years – and he’s now much better, thankfully. Also, there’s that tiny little two-word moniker that he finally gets to wear – World Champion. As we were talking, and he was regaling me with story after story after story, it became evident that a smaller “What Could Have Been … What Should Have Been” piece could be written – using mostly just his words to tell those stories. What could have been … the direction the Cubs’ farm system was heading during the Dallas Green years. What should have been … up 3 games to 1 with a lead in Game 6 of the 2003 NLCS. And finally … winning the World Series in his 34th year in the organization. Blitzer will be back at it later this week when his in-season professional coverage begins. I’ll be back at it with another Blitzer story soon. But until then, to whet the appetite, I’ll call this a Billy Blitzer prequel in three parts. ***** It Coulda Happened … Not to take away anything from Theo, Jed and the current group, but it’s well known that the Cubs’ arrow was pointed upward when I started with the organization as an intern in 1986 – and the curse could have been lifted years ago. The operative words are “could have.” Tribune Company purchased the team from the Wrigley Family in 1981 and installed Dallas Green as the general manager. The team came close to the Promised Land in 1984 – going up 2 games to 0 in the best of 5 NLCS against San Diego – and had an extended run at clicking on their draft selections. Consider this list of players selected from 1982-1987, and think how things might have played out if they had been kept together – along with a certain second baseman named Ryne Sandberg who was acquired by Green early in his GM tenure:

“It’s a shame that Dallas just passed away,” Blitzer said. And now I’ll let Mr. Blitzer take it from here. “When I first came in, I was a young scout. I felt at the time that Dallas had us going in the right direction – and that eventually, we would have won. Gordy Goldsberry was the scouting director, and we were drafting very well. We had young players – and then just like that, Dallas was out. Jim Frey came in and traded away a lot of those young players. Every time you change regimes, it’s a new game plan, and we couldn’t get our footing. “After Dallas got let go from us – even though he later was the manager of the Mets and the manager of the Yankees – I had never spoken to him again until a couple years ago. He was working with the Phillies as an advisor, and this kid, Aaron Nola – who was their No. 1 pick – was making his professional debut for the Clearwater Phillies in Lakeland (Florida), and I was covering the Phillies organization. I was in the ballpark, and Dallas comes walking in with Charlie Manuel. “I see him, and I walk right over toward him. As I got closer, Dallas sees me – and in his big, booming voice – he yells out, ‘Billy Blitzer, I haven’t seen you in years.’ “And I said, ‘Dallas, I’ve seen you through the years from the stands, but I don’t go down on the field and bother anybody.’ “Then I put my hand out and said, ‘I’d like to shake your hand and thank you.’ “We shook hands, and he said, ‘Thank me for what?’ “I said, ‘Dallas, I’m still with the Cubs, and I’ve been here for over 30 years. And I want to thank you for hiring me.’ “And he said, ‘Well, Gordy knew what he was doing.’ “I said, ‘But you were the GM, and you had to give the OK to hire me. And I’ve made a career out of it here. And from the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you.’ “I got a little choked up as I said it to him. And he kind of got choked up, too, because he knew I really meant it. With him just passing away, it means a lot to me that I was able to say that to him. “I just feel that if Dallas had been given more time, we would have won. We’ve had a lot of good people here. Some people did it the right way. Other people … I didn’t think did it the right way, and I don’t know how much hope there was for us to win.” ***** It Shoulda Happened … I think it’s safe to say that if you’ve read this far, you remember the 2003 NLCS. The Cubs had taken a 3-games-to-1 lead over the Florida Marlins before dropping Game 5. In Game 6, the Cubs were leading 3-0 in the top of the 8th inning – five outs away from the World Series. That was as close as they got … until 2016. Anyway … during his spring coverage this March, Blitzer had a chance meeting with the leftfielder who was involved in the infamous foul ball incident. “I’m sitting behind the plate in the next-to-last row of the scout section, toward the end of the aisle, Blitzer said. Like a good storyteller, he gave all the pertinent facts. “There were a couple empty seats behind me when the game was about to start, then two people sat down. “I turned around, and one of them was Moises Alou. I don’t know Moises – he’s never met me, and I never met him – but I recognized him. I have to give him a lot of credit. Throughout the game, people kept coming over to him asking for his autograph, asking him to pose for pictures. They didn’t wait until the end of the inning. They were just disruptive. There’s no way he could have watched any of the game. “In about the sixth inning, a guy sitting a couple rows in front of us happens to turn around and realizes that Moises is sitting there. The guy gets up, walks up to him – and he says, ‘Mr. Alou, you were a great player, but you should have caught that ball.’ He says it just like that, then turns around and goes back to his seat. “Now I’m watching this whole thing. When the guy walked away, Moises put his head down. Then he looked up at me. Six innings, we hadn’t said one word to each other. “He looked at me and said, ‘That’s all I’ll ever be remembered for … that I should have caught that ball.’ “So I said to him, ‘Yeah, you and me both.’ “He said, ‘What do you mean, you and me both?’ “I said, ‘I’m with the Chicago Cubs. I’ve been here for 35 years. All I’ve had to listen to were two things – you not catching that ball and the ball going through Leon Durham’s legs.” And then – please try to mentally visualize the New York accent here – Blitzer said: “But I don’t have to listen to that anymawhhhh, becawz we finally wuhn.’ “He patted me, smiled and said, ‘I’m really happy for you.’ “He spoke to me after that. I told him, ‘I’ve had to listen to that, also. You’re not the only one.’ “It’s like the monkey’s off my back – not only my back, but everybody’s back. The things I had to listen to for 34 years. All the jokes about the Cubs and everything else. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate it that we won. And that I’m finally getting a ring.” ***** It Did … In 34 years with the Cubs, Blitzer has pretty much seen everything and done everything. Starting in the early hours of November 3, 2016 – New York time – he has for the first time experienced what it’s like to be a champion. “It really was nice in spring training,” he said. “On the night we won, within seven minutes, I had 100 texts or emails from people all around the country … people that know me. And here in spring training, I’ve run into other scouts. When they first saw me, it was ‘Congratulations. Hey, world champion.’ It was really nice to hear, but the one thing that really hit me … whenever I met these people, the first thing they’d say to me was, ‘You know, when your team won, you were the first person we thought of.’ They know I’ve been here so long. “Not many people stay with one team for so many years. And when I walk in the ballpark, it’s ‘The Chicago Cubs are here.’ It’s not ‘Billy Blitzer’s here’ … it’s ‘The Chicago Cubs are here.’ “And then there’s the other thing. Everybody was asking me, ‘When are you getting your ring? When are you getting your ring?’ I say, ‘The players get it April 12. I’m sure we’ll get it right after.’ “All the scouts that have gotten rings before tell me, ‘You better have a box of tissues, because you’re going to start to cry when you get it.’ And I know I will. When we won, I broke down and cried. Even now, when I watch videos of us winning, and I watch videos of people in Chicago, I get all choked up. Every time I see it – and it hasn’t stopped yet. It means that much to me. “I’ve thought about it. If I had gotten the ring early in my career, it wouldn’t mean as much as it does right now. Because I’m towards the end of my career. I’ve scouted 42 years, 35 with the Cubs. You think about all the games I’ve been to. All the hotels. All the miles. All the bad food you’ve eaten through the years. You always dreamed. You always hoped that your team could win. Coming towards the end of my career, it means so much more – because you realize how much has gone into it through the years. To finally achieve it." |

Details

About MeHi, my name is Chuck Wasserstrom. Welcome to my personal little space. Archives

August 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed